A Man Feared by the 21st Century:

Saint Maximilian Kolbe from the Starvation Bunker in Auschwitz

See also The First-Class Relics of St Maximilian Kolbe

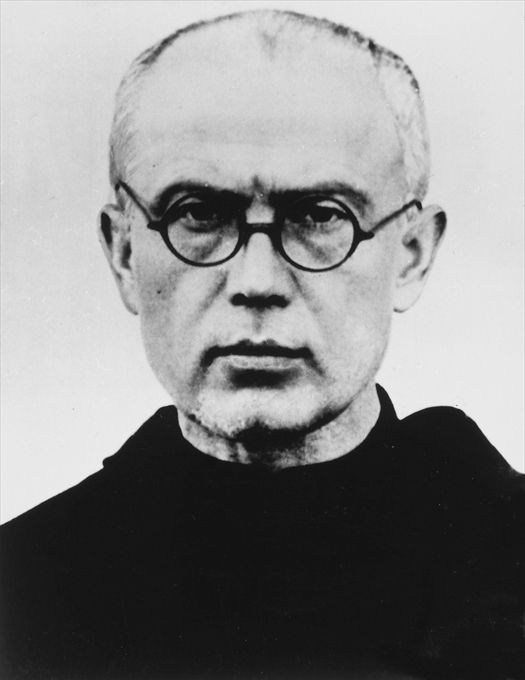

Maximilian Kolbe (1894-1941) was a Polish Franciscan, priest, visionary, spiritual director, missionary, scholar, writer, journalist, publisher, and founder and superior of monasteries in Poland and in Japan.

He was born in a family of poor weavers in Zduńska Wola near Łódź in Poland. He entered the Franciscan order and studied in Lwów. He continued his studies in Rome, where he earned two doctoral degrees in philosophy and theology. He founded the “Militia Immaculata” [or Knights of the Immaculata] in 1917, and was ordained priest in 1918. Upon his return to Poland he was a professor in Crakow and began publishing a monthly magazine promoting devotion to Mary Mother of God, under the title Knight of the Immaculatae. In 1927 he founded a new Franciscan monastery in Niepokalanów near Warsaw, which soon developed into a large convent and publishing center. He was the superior of Niepokalanów from 1927-1930.

From 1930-1936 Fr. Kolbe worked as a missionary in Japan, founding a monastery – Mugenzai no sono – a seminary, and a publishing house in Nagasaki.

In 1936, he returned to Poland, became again superior of Niepokalanów, and accelerated its growth. Within a few years Niepokalanów became the largest monastery in the world, housing more than 700 friars. At the same time it became a large media complex publishing several religious magazines and a daily, Mały Dziennik (Little Daily). In 1938, Niepokalanów printed sixteen million copies of its publications. “Radio Niepokalanów” was initiated and “Television Niepokalanów” was planned.

The war interrupted this tremendous activity. Fr. Kolbe was arrested by the Gestapo in September 1939, along with several dozen of his brothers. Released about three month later, and allowed to return to Niepokalanów, he transformed the monastery into a refuge that sheltered thousands of displaced, homeless, and persecuted people, among them 1,500 Jews.

He was arrested again in February 1941, and imprisoned in Warsaw. On May 28, 1941, he was sent to the Nazi concentration camp, Auschwitz. The camp functioned, at that time, as an extermination site for Polish elites, including the clergy. When a prisoner escaped from the camp, the Germans punished the unit to which he and Father Kolbe both belonged by selecting ten prisoners to be starved to death. Fr. Kolbe volunteered to die in the place of one of his fellow prisoners. He passed away on August 14th, 1941. He was beatified by Pope Paul VI in 1971, and canonized by Pope John Paul II in 1982. The year 2011 marked the 70th anniversary of Fr. Kolbe’s death in Auschwitz. Celebrations of the anniversary were held all over the world.

Based on research conducted in Crakow, Harmęże, Auschwitz and Niepokalanów in Poland, as well as in Nagasaki, Japan, I wrote three plays on Fr. Kolbe: Maximilianus, Father Maximilian’s Cell and My Son, Maximilian. All of them narrate the life and deeds of Fr. Kolbe, approached from different angles. Maximilianus is a large, epic, biographical play with many characters and various settings. The action of Father Maximilian’s Cell takes place in Fr. Kolbe’s cell in Niepokalanów, just before his arrest; in flashbacks he returns to significant events of his life. My Son, Maximilian focuses on the character of the saint’s Mother, Mariana. All these plays were published in Poland and produced or read in churches in Poland, the United States and Canada. The readings ─ modeled on reading of the Passion of the Lord Jesus in the Holy Week ─ were done by three lectors.

The last part of all three plays is an “apocrypha” narrating Fr. Kolbe’s suffering, persecution and death in the Nazi concentration camp, Auschwitz. Let me quote a part of it in which I tried to capture the essence of Fr. Kolbe’s personality and spirituality:

LECTOR 1: In the evening the Lagerführer Fritzsch appeared in front of the men and announced:

LECTOR 2: The fugitive was not caught. Ten are going to be selected for death by starvation in the bunker.

LECTOR 1: It was a horrible death that came by slow degrees. The Lagerführer begun to casually walk between the rows, and from time to time he pointed his finger at a prisoner, whose number was put down by another SS officer, Rapportführer Gerhard Palitzsch. Two other SS men immediately yanked the sentenced prisoner out of line and stood him against the wall. The tenth man was chosen; it was a young man who began to cry and screamed:

LECTOR 2: So, am I to abandon my wife and orphan my two children?!

LECTOR 1: At that moment Father Kolbe stepped out of the row. Kapo Krott dashed toward him shouting:

LECTOR 2: Get back! Get back to your row!

LECTOR 1: And he lifted the club to strike him. However, Father Maximilian looked at him calmly and with enormous power in his eyes, and said:

PRINCIPAL LECTOR: I want to speak with the commandant.

LECTOR 1: And something unprecedented happened, because the kapo lowered his club and stepped back, while Father Maximilian moved towards the Lagerführer. The Lagerführer reached for his gun-holster and shouted:

LECTOR 2: Steh! Was is los?

LECTOR 1: That is, Stop! What is this? But Father Maximilian kept on walking towards him. He stood in front of him and took off his cap, according to camp regulations. The German, taken aback and stunned by Father’s behavior, didn’t pull his gun and shoot him on the spot as would be the custom for this SS officer, but said:

LECTOR 2: Was wünst dieses polnische Schwein?

LECTOR 1: That is, What does this Polish pig want? To which Father Kolbe replied in a quiet voice:

PRINCIPAL LECTOR: I want to die in the place of one of the inmates selected.

LECTOR 1: The Lagerführer asked him:

LECTOR 2: Für welhen?

LECTOR 1: That is, For which one? And again it was an unprecedented thing, for a Lagerhührer, the ruler of life and death, in his own German eyes a superman, entered into a dialog with a prisoner, who, for him, was not a man at all, only number 16670. And that number replied to the German clearly and convincingly, explaining the matter to him according to his mentality:

PRINCIPAL LECTOR: I want to go to the bunker for this young one. I’m old and ill, my life is not needed. He is young, has a wife and children.

LECTOR 1: At that the Lagerführer asked:

LECTOR 2: Was bist du?

LECTOR 1: Which means, Who are you?

PRINCIPAL LECTOR: I am a Polish Catholic priest.

LECTOR 1: This was Father Maximilian’s reply in German language as well as his testimony: Ich bin ein polnischer katholischer Priester — I am a Polish Catholic priest. And a third unparallel thing happened, unknown in the chronicles of the concentration camps, and never repeated. The Lagerführer, Hauptsturmfürher SS Karl Fritzsch, submitted himself to the will of a prisoner. He did not kill him; he did not simply include him in the group of those already sentenced, as one more sent to die, but barked:

LECTOR 2: Heraus!

LECTOR 1: Which is to say, Go there! In this way Father Kolbe delivered himself to death for a man unknown to him. And Father Kolbe joined the group of sentenced prisoners. Rapportfürher Palitzsch followed him and in his note-book he crossed the number of the pardoned, number 5659. The man bearing this number was Franciszek Gajowniczek, a sergeant of the Polish Army, who found himself in a POW camp after the campaign of September 1939. He had escaped, was caught, and sent to Auschwitz. He was ordered to return to his row, while number 16670, Maximilian Kolbe, was put down in the Rapportfürher’s note-book. Right away the SS men ordered the sentenced to take off their footwear and led them to the starvation bunker. One of them was so weak that he staggered, so Father Maximilian enfolded him in his arms and supported him on the way.

The Germans led them to barrack number 11. They ordered them to strip. They herded them to a tiny basement cell – number 18, very low, about 8 feet by 8 feet, with one small barred window near the ceiling. It had a concrete floor and in the corner a bucket for waste. There they were to die by starvation. The SS men shut the iron door.

It is good to remember Fr. Kolbe, an extraordinary yet simple man, especially in contemporary culture, where such values as honesty, truth, and love for the neighbor are so often disregarded and forgotten. It is good to remember him, for he is a great role-model who might teach us how to live honestly and lovingly.

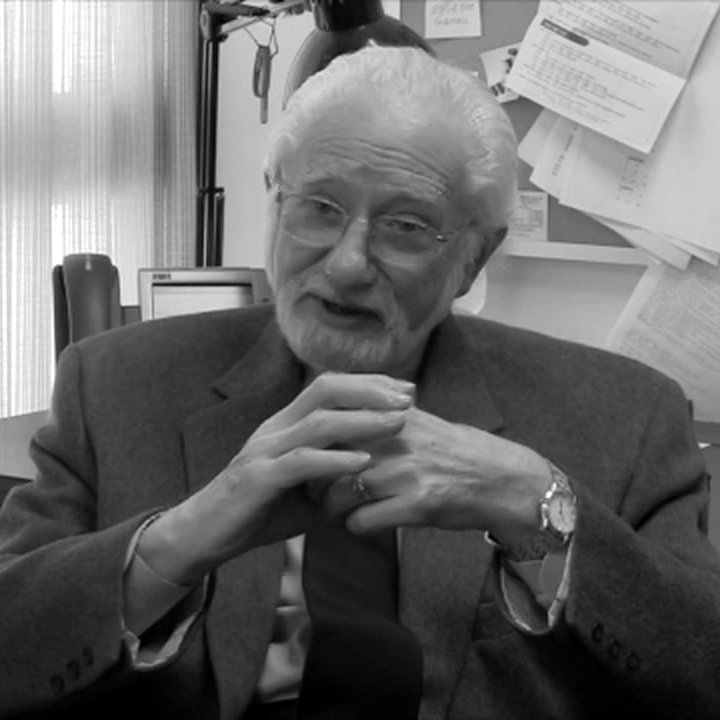

Dr. Kazimierz Braun is a writer, theatre director and scholar, and a professor at the University at Buffalo. He has taught at universities in Poland and the United States. He has published more than 50 books, including scholarly works, novels and dramas, and he has directed more than 150 theatre and television productions in many countries. He was both the General and Artistic Director of the Contemporary Theatre in Wrocław. He has received several awards and honors for scholarship, writing and directing, such the Guggenheim, the Fulbright, the Turzański, the Japanese Foundation, and others.

For information on the plays on St. Maximilian Kolbe, write an e-mail to the author: kaz@buffalo.edu